Good animal welfare is defined, for the purposes of this article, as when an animal has both its physical needs (adequate housing, food, and water, and good health) and mental needs (able to perform normal behaviours, not frustrated, fearful, or distressed) met.

There are many perspectives on animal welfare. Some may think that an animal that is producing well has good animal welfare while others think that animals with a high level or production must have poor welfare. In reality, the link between production and welfare is more complex.

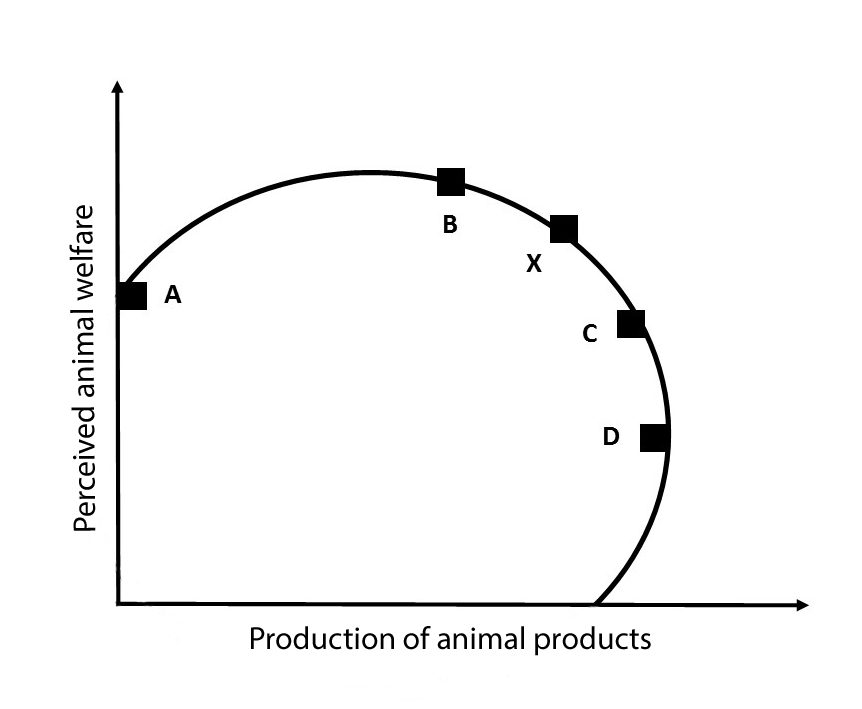

This graph, adapted from one created by Richard M. Bennett from the University of Reading in the UK, represents a simple theory on the relationship between welfare and productivity.

As welfare increases from point A to point B, productivity goes up with it. For example, providing veterinary care improves welfare by preventing animals from suffering from disease but also improves productivity by reducing the amount of energy an animal needs to use to fight disease, allowing this energy to be used for increasing productivity.

As productivity increases (between points B and D), eventually animal welfare begins to drop off. For example, broilers (meat chickens) are extremely efficient at producing a large amount of meat in a short time period, but this increased mass can lead to leg or foot problems such as lameness. Leg and foot problems can cause pain, reducing welfare.

In this graph, at point D welfare is so low that the animal is not producing well. When an animal’s basic needs are not met, they cannot be productive. An example of this is feeding calves very small milk allowances (four litres per day or less) in cold temperatures. This reduces welfare by causing feelings of hunger in the calf as well as reduces productivity because the calf uses all the energy to keep warm and has no energy left for growth. Neither the animal nor the producer benefit from this way of raising livestock.

Livestock need a minimum level of care to be productive. Yet, animals can still produce when their welfare is not ideal. An animal needs to have very low welfare before it completely stops being productive. Overall, an animal that is not producing well likely has impaired welfare. However, just because an animal is producing, does not automatically mean it has good welfare. Welfare cannot be measured by productivity alone.

From an economic perspective, the ideal relationship between productivity and animal welfare can be found somewhere between point B and point D. It is up to society to answer the ethical question of exactly where between point B and point D we want to be. As producers, we need to keep this balance and consumer preference in mind as we continue to strive towards raising productive animals with good welfare.

Bennett argues that we are currently at point C; society has accepted a lower level of production because we believe that animal welfare is important and should not be ignored. As consumers become more concerned about the welfare of the animals producing their food, we may be moving to point X, where we are willing to lower production efficiency more and place a greater value on animal welfare. This can be seen in the push towards “cage free” foods. Many consumers are willing to accept lower production in favour of phasing out much of the confinement housing that provides efficiency to many commodities.

Consumers want to know livestock have good welfare while producing safe, healthy, and affordable food. As an industry, we need to work together with consumers to find the balance between welfare and production.