Ca seous lymphadenitis (CL) is a chronic infection of sheep and goats caused by Cornebacterium pseudotuberculosis bacteria. This contagious disease is best known for abscesses (buildup of pus) in the external lymph nodes of the neck and abdomen. However, CL abscesses can also form internally in the lungs, udder, liver, and kidneys. Goats with CL can lead to economic losses due to carcass condemnation, reduced milk production, and weight loss. Additionally, producers who have a herd free of CL generally avoid purchasing infected goats or goats from an infected herd, which can reduce the value of breeding stock. Hides from slaughtered goats may also be worth less due to CL blemishes.

seous lymphadenitis (CL) is a chronic infection of sheep and goats caused by Cornebacterium pseudotuberculosis bacteria. This contagious disease is best known for abscesses (buildup of pus) in the external lymph nodes of the neck and abdomen. However, CL abscesses can also form internally in the lungs, udder, liver, and kidneys. Goats with CL can lead to economic losses due to carcass condemnation, reduced milk production, and weight loss. Additionally, producers who have a herd free of CL generally avoid purchasing infected goats or goats from an infected herd, which can reduce the value of breeding stock. Hides from slaughtered goats may also be worth less due to CL blemishes.

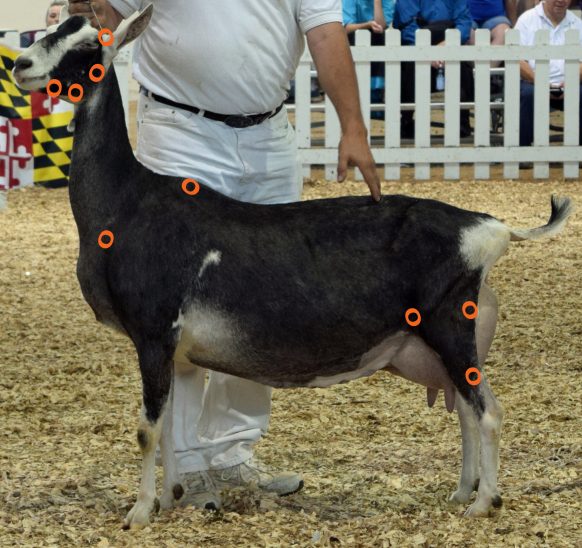

Lymph nodes play an important role in the immune system – storing white blood cells and filtering foreign particles to detect infections. There are many lymph nodes throughout the body. In humans, two lymph nodes are found under the chin and you (or your doctor) may find them swollen if you are sick.

Infection

Goats become infected when the bacteria enters through an open wound or mucous membranes (e.g. eyes, nose, and mouth). Swollen lymph nodes are typically not detectable for two to six months after initial infection. Most often, the first abscesses are in the head and neck area, as the head is most susceptible to injury (e.g. splinters from wooden feeders, combat wounds, scratching at parasites or flies) and if a goat puts their injured head where a goat with a draining abscess has (e.g. feeders, milking stanchion, handling equipment), the infection will spread.

As the lesions in lymph nodes grow, abscesses containing creamy white, yellowish, or greenish-coloured pasty pus, rich in bacteria form. These abscesses displace normal tissue and can cause difficulty breathing, eating, and ruminating, depending on the location of the abscess. If there are abscesses in the lung, goats often exhibit signs of respiratory distress and wasting which will reduce productivity and can eventually lead to death.

Transmission

The infection is transmitted directly to other herd members when external abscesses rupture as they increase in size. Nasal secretions can also be a source of infection as lung lesions grow, rupture, and expel their contents. CL can also be spread indirectly through contaminated equipment and surfaces in the barn. Goats infected with CL should be milked last, and all equipment cleaned and sanitized after use. The infection is potentially transmissible to humans, so wear protective clothing when working with infected or possibly infected animals. This protects both humans and the rest of the herd.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally based on finding a fairly firm abscess in the location of a lymph node. Generally, if a herd has a history of CL, this is enough to assume the diagnosis. If there is no history of CL in the herd, a biopsy of the abscess can be sent for laboratory testing. If a goat is suspected of having CL, it should be isolated and treated as contagious until the cause of the swelling is determined. See Ontario Goat’s “Best Management Practices for Commercial Goat Production” for isolation procedures.

Treatment

Unfortunately, infected animals remain infected for life, and CL does not respondto most antibiotics. Studies on the appropriate antibiotic, dose, or withdrawal times of various antibiotics used experimentally to attempt to control CL in goats are not available, so are not recommended as treatment. Use of antibiotics to treat infections that do not respond to antibiotic treatment, such as CL, can increase the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance as well as waste time and money.

Abscesses can be drained or surgically removed. Draining leads to contamination of the environment, requiring the goat to be isolated until the abscess heals completely – approximately 20-30 days later. The environment then needs to be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Surgical removal is not practical for most producers – it removes the abscess without draining it so the bacteria is not released into the environment, but requires the goat to be anesthetized for the delicate surgical procedure. Consult with your herd veterinarian about whether draining or removing abscesses is the right choice for your herd.

There is a CL vaccine available in the United States for goats. In Canada, there is a vaccine for sheep, but it is not recommended for use in goats due to the high frequency of adverse reactions such as fever, swelling at the infection site, and abortion.

Testing

Blood testing is available to determine if goats have an early stage or internal infection of CL. Work with your herd veterinarian to determine the best way to include CL testing in your protocol for new stock or stock returning from off-property.

Control and eradication

The best defence against CL is to maintain a closed herd or subject all new animals or animals returning from off property to a strict isolation protocol to prevent the infection from entering the herd.

In herds where CL is already present, control and eradication can be difficult. A strict testing and culling protocol or separation of infected and uninfected goats can be helpful. Managing kids to prevent contact with CL positive dams and heat-treatment of colostrum or pasteurization of milk can help prevent spread. If you choose to control or eradicate CL, work with your veterinarian to develop an appropriate management program for your herd.

Since the bacteria that causes CL can survive in the environment for several months, prevention and disinfection strategies are key to controlling the spread of this infection. Although abscesses can be visible, many goats who only have internal lesions go unnoticed. Therefore, detection of caseous lymphadenitis involves monitoring animals for clinical signs, sending biopsies of abscesses for testing, and blood sampling of goats that do not exhibit outward signs of disease.

Prevalence

Caseous lymphadenitis is likely widespread in goat herds. A studyin Quebec tested 152 dairy and meat goats found dead or euthanized on farms. CL abscesses were found in 24.3 per cent of animals. Further, 84.6 per cent of herds had at least one goat affected by the disease. Over half (54.1 per cent) of CL cases had only internal abscesses, meaning the producer likely didn’t know the goat was infected with CL. The CL infection itself caused only a minor amount of deaths (3.9 per cent) of the goats in the study[1].

Summary

Despite the fact that CL is not a leading cause of morality, potential production losses and concern for animal welfare should encourage producers to reduce the occurrence of the disease. Producers should aim to prevent CL from entering their herd by practicing strict biosecurity and screening all new stock or stock returning from off-property. Producers can control and eradicate CL from their herd with careful management and maintaining separate infected and uninfected herds.