A small ruminant adult mortality project is underway, hoping to identify the common causes of mortality and provide guidance on prevention through post-mortem examinations. Post-mortems are veterinary exams performed after an animal has died. Typically, these examinations are done to determine the cause of death.

Jeanette Cooper, a Master of Science student working on the project, told attendees at the Ontario Goat Annual General Meeting & Producer Education day, “We don’t really know a lot about what is affecting adult small ruminant mortality.” Producers are not regularly asking their veterinarians to perform post-mortem examinations, and sometimes veterinarians aren’t getting good samples from these animals to send to labs. This means there are mortalities occurring on-farm with unknown causes. If producers don’t know why an animal died, they can’t take steps to avoid further losses.

The project is very simple for producers. Ask your herd veterinarian to sign up for the project now, before you have an animal for post-mortem. If a goat over one year of age dies on your farm, call your veterinarian to perform an exam. They will have instructions and a tool kit from the project to help them perform the examination. They will send samples to the University of Guelph’s Animal Health Laboratory, who will perform $400 worth of diagnostic testing. The project also pays your herd veterinarian up to $175 for their services. This means you can get a diagnosis on a dead goat for little or no cost. The project will send results to your veterinarian who will discuss them with you, and can help you determine the best way to avoid another mortality.

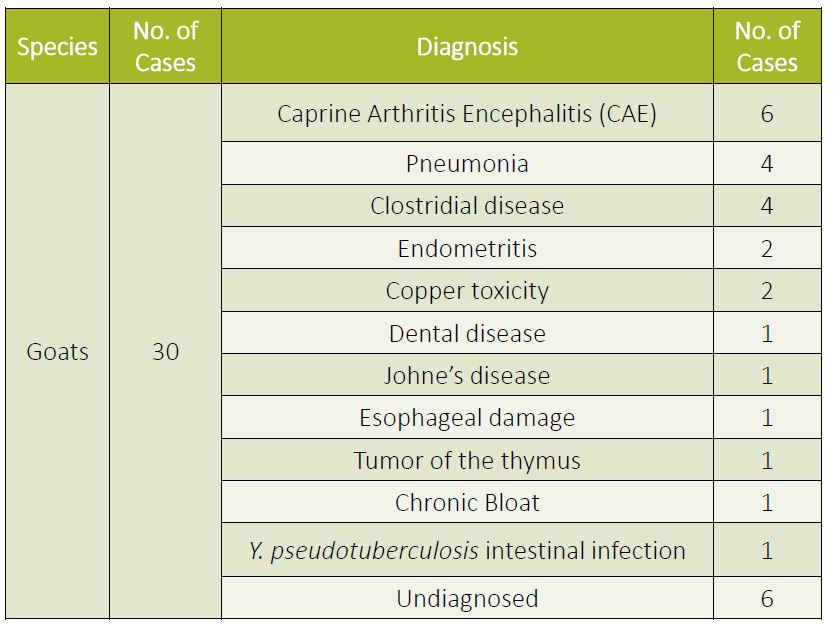

As of February 2018, 30 goats have been examined, and Caprine Arthritis Encephalitis, pneumonia, and clostridial disease have been the primary causes of death. The researchers are comfortable with their ability to confirm a cause of death – only six cases have been undiagnosed.

An interesting finding from the project so far was that goats were experiencing copper toxicity. Jeanette noted that most think that copper toxicity is not a problem for goats, but these results prove otherwise.

For both clostridial disease and copper toxicity, by the time you notice symptoms, the goat is too far gone to recover. This underscores the importance of making sure that all mortalities are diagnosed. It was too late to save the one dead goat, but it may not be too late to make changes to protect the rest of your herd.

The project is looking for 100 additional cases, and then will be holding focus groups with the broader goal of understanding small ruminant herd health and veterinary-patient-client-relationship (VCPR) to improve health in the goat and sheep industry as a whole.

For more information go to the project website at https://www.uoguelph.ca/srmort/.